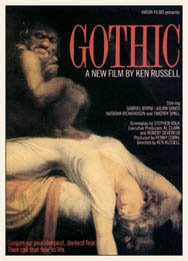

Gothic

(UK, 1986, 87 min.)

Starring Natasha Richardson, Gabriel Byrne, Julian Sands, Miriam Cyr, Timothy Spall.

Written by Stephen Volk.

Directed by Ken Russell.

Author's note: This was originally written as part of the

My college girlfriend was very much into poetry and the romantics in particular. I am not nor have I ever been particularly impressed with the art form, and though I can appreciate it from time to time, the romantic stuff has always struck me as overly florid and self-indulgent, though admittedly this may be a by-product of what I know, or at least think I know, about the people who wrote it, absinthe-swilling twits that they supposedly were. My girlfriend always used to say to me whenever I mocked them, particularly her not-so-secret crush Mr. Bysshe Shelley, that if we were living in the same period, Shelley and I would almost certainly be best friends as our natures, as she saw it anyway, were practically identical. I would usually respond by telling her that if I ever came across Shelley in a dark alley, I’d kick his stanza-writing ass all the way back to Queen Mab. I was half-kidding, of course, in that sadistic, tormenting way we reserve for our nearest and dearest friends and loved ones. On the other hand I was also half-serious, because what I’ve read about the behavior of the romantics, Byron and Shelley in particular, suggests to me the very worst aspects of the creative type: the kind that assumes that being a free spirit is the same thing as running about like an idiot. Were these people really like this? History would seem to suggest that it’s so. And let me tell you, he said getting to the matter at hand and not a moment too soon, if they were anything like they’re portrayed in Ken Russell’s Gothic, then a can of whup-ass would not have been sufficient. I’m guessing we would’ve had to open up a gallon barrel. (Well, a sound spanking would have been in order at the very least. I’m such an old softy.)

We begin with poet extraordinaire Percy Shelley (Sands) and Mary “Not Yet Mrs. Shelley” Godwin (Richardson) visiting Lord Byron (Byrne) at his estate in Switzerland. Also in attendance is Mary’s precocious (read: slutty and twerpy) step-sister Claire (Cyr) and Byron’s extremely gay personal physician Dr. John Polidori (Spall), and it’s a wonder given the treatment Byron inflicts on the doctor that Polidori doesn’t go Kevorkian on him. But then love is a strange thing, isn’t it? And Polidori indeed loves Byron, as much as Byron loves Shelley and as much as Shelley loves quaffing wine, chasing tail and generally running around like a spastic freak.

As those of you literarily-inclined may have guessed, this is a dramatization of the famous weekend where these loony luminaries challenged each other to write their own horror stories, resulting in Polidori’s The Vampyre and, more famously, Mary’s Frankenstein. In the course of the film the group performs a séance whereupon bizarre things begin to occur, scaring the bejeezus out of them and convincing them that they have somehow brought something that was dead back to life. Something that isn’t terribly pleased with having been disturbed and that would like to express its displeasure personally. It proceeds to do this by forcing them to face up to the things that disturb them most, including Mary’s heartbreak over the death of her prematurely-born baby that has been speculated is what caused her to write a story about a man who brings life back into dead flesh.

This is a Ken Russell film. If you don’t know what that means, it generally involves freaky, flamboyant imagery, often religious in nature, explicit sexuality, and lots of pseudo-philosophizing on such topics as, not surprisingly, religion and sex. As such the members of this group, with their conflicting views on the former (Shelley is an avowed atheist, Polidori a devout Catholic, etc.) and fair consensus on the latter (free love is all the rage, dontcha know), are perfect Russell fodder.

The visuals are, as per usual, something to behold. Russell peoples Byron’s mansion with a number of artificial humans: a mechanical harpsichord player; a walking suit of armor with a tremendous phallus; and a robotic woman with eyes where her nipples should be that repeatedly haunts Shelley. The significance of this last one frankly eludes me, though it could easily be a well-known image from his poetry, possibly even from something I may have read, as romantic poetry tends to evaporate off the surface of my brain at a remarkably rapid rate. But the overall reference here is obvious: manufactured life. This theme pops up in other slightly more subtle places as well, such as a shadow on the wall of a tree struck by lightning, presented in such a way as to make it look like a living being in great pain. The overall effect is for us to get a glimpse inside of Mary’s mind, the images serving to help us imagine how she came up with the idea of an obsessed man sewing limbs to torso and getting ready to grab a life force and tear it out of the sky.

The director also makes good use of the unrelenting tragedy that seemed to befall these people, most especially in the climactic sequence in which Mary has a vision of the future, including the deaths of Polidori, Byron and Shelley and the birth and death of her and Shelley’s second daughter. This sequence lends the piece a sincere poignancy, much needed by this point, as it curtails, if only for a minute, the factor that makes this film a tough sell.

Not unlike the common problem in slasher films, in which the characters are so obnoxious that you have absolutely no problem watching them get picked off one by one, the artistes in Gothic are presented as such decadent twerps, overgrown children whose minds, despite their grandiose musings about God and such, rarely rise above their waistlines, that watching them get the shit scared out of them seems somehow more appropriate than it does anything else; a much-needed lesson. Was this intentional on Russell’s part? I tend to doubt it. I think for the most part he admires these people (‘these characters’ would be more apt as I still can’t say for sure how close they are to the true figures). At the very least I would say that he feels sympathy for them, and this comes out most clearly in the ending. The new day dawns and everything has seemingly returned to normal, the events of the previous evening no more than a particularly vivid and freaky acid trip, and yet we’ve gotten a glimpse of the terrible things that await them in the future and as the scene morphs from the past to the present, with tourists walking across the lawn of Byron’s mansion (one of them played by the director), we realize that those awful things have already happened. That Shelley and Polidori have already discovered whether or not God exists, even if they can’t tell us about it.

As for me, sympathy? Sure, as I would feel sympathy for anyone who suffered some of the fates that befell these people. Admiration? Well, no. Not really. I confess that in preparation for writing this review, I pulled out some books with Byron and Shelley’s work in them and I found that I got a bit more out of them than I had previously. Would Percy and I be best friends? I doubt it. Would I beat him up? Of course not.

A few good noogies would probably suffice.

Post Script: I’m getting a picture in my head: a picture of one Monsieur Bergerjacques glaring intently at his computer screen and thinking of what would be the cheapest, quickest way of having me whacked. Sitting there on his inflatable donut, which he has to use owing to the copy of Obsession: A Taste for Fear still lodged in his ass (I swear to God, guys, I only asked him to watch the thing!), he thinks, “All this time I was waiting for some pain payback, and he gives me THIS!!!!” Yep. Sorry, BJ. While I can’t claim to have enjoyed this film, I actually did like it a bit more than the first time I saw it, and it gave me some interesting things to think about. Almost a rewarding experience when you come right down to it. And I now realize that this PS, intended as a way of smoothing things over, has probably in fact made them much, much worse. So I’ll just say good day, sign off and spend the next week remembering to stay away from windows.

Go back to Plate O' Shrimp