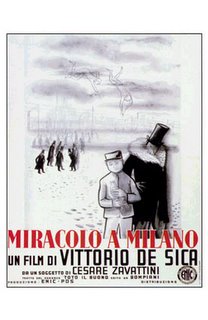

Miracle in Milan

(1951, 95 min.)

Starring Francesco Golisano, Paolo Stoppa, Emma Gramatica, Guglielmo Barnabo, Brunella Bovo, Anna Carena, Arturo Bragalia, Erminio Spalla, Jerome Johnson

Written by Vittorio De Sica and Cesare Zavattini, from a novel by Zavattini, with additional material by Suso Cecchi d’Amico, Mario Chiari and Adolfo Franci

Directed by Vittorio De Sica

An older woman, Lolotta (Gramatica), finds a baby in her garden and raises him as her own. When she dies he’s placed in an orphanage, from which he emerges a stunningly idealistic young man, Toto the Good (Golisano). Having no prospects and nowhere to go, he takes up with a ragtag band of homeless, whom he encourages to build a shanty-town, the residents of which include a man who thinks himself better than all the rest and gets along with no one, a family with similar airs, who are ultimately just hucksters and who have a housekeeper who takes a shine to Toto, and a black man and a white woman who must pretend not to be a couple owing to their mixed races.

A rich man buys the property the town rests upon, and while he is open and understanding about the plight of the residents at first (partially out of fear of them), when it is discovered that there is fuel to be had under the land, it isn’t long before he’s called out the cavalry to move them out and start drilling. Fortunately for the residents, Toto’s dead adopted mother pays him a visit to give him a heavenly dove that allows him to grant wishes. It’s very effective in driving away the capitalistic forces that darken their doorway, but it also, to no surprise, begins to corrupt the very people it was sent to save.

De Sica was one of the founders of the Italian Neo-Realist movement, which was a post-war school that strived, much like the Dogme 95 movement spearheaded many years later by Danish filmmaker Lars Von Trier, to slough off film conventions established by Hollywood through the use of a handful of particular facets meant to alter the very face of cinema. The Italians weren’t quite as assertive as the Scandinavians (whose fervor was built right into their name after all), at least in as much as they didn’t bother to write up a manifesto, but their aim was clear: to construct a cinema that looked like real life, more in step with what the viewer’s eyes actually see when they’re not confined within the theater’s walls, and, in the process, give a voice to the trodden underclasses.

It’s further interesting to note that it didn’t take long for both schools to begin bending or even casting aside their own rules, this film being a perfect example of De Sica’s break from form, at least in terms of tone. Working from a script written by, among others, Cesare Zavattini, who adapted from his own novel, De Sica uses the story as a way of expressing his own contempt for that often astonishingly shown towards those whose lives had been decimated by the war. But instead of the heartbreaking pathos of such films as his classic Bicycle Thief, he infuses the story with fantastical whimsy, from as early on as the few short opening scenes when he establishes the relationship between the old woman and her charge with remarkable adeptness and economy. The shanty town and the magical defense thereof provide him the opportunity for numerous sight gags and truly funny bits (I got a particular laugh out of the opera-singing soldiers). Of course, in true post-war Italian fashion, and as befits the story, it’s not all fun and games. The resolution of the mixed race couple’s situation is like something co-penned by O. Henry and Rod Serling. Still, overall, this wouldn’t be a bad film to start with if you wanted to try to get a kid interested in foreign cinema.

I will add one caveat, and expose my inherent cynicism in the process. I deliberately neglected to mention that when Lolotta finds the boy in her garden, he is, in fact, in a cabbage patch. Yes, Toto is a literal cabbage patch kid. And while the abiding cutesiness that bygone fad may conjure up doesn’t stain this film, there is a streak of ‘spirit will prevail’ up-ness similar to the one that runs through films like Lasse Halstrom’s Chocolat, for example. Your tolerance for such untrammeled optimism may color your enjoyment of the film. And while it’s been correctly pointed out that the film’s final image (and perhaps Toto’s starry eyes in general) can be seen as an expression of deep cynicism, it’s presented so joyfully it almost seems churlish to cast it in such a light. Perhaps after the utter bleakness of films like the aforementioned Thief, and such other neo-realist touchstones as Rossellini’s Open City and Visconti’s La Terra Trema, some good will was what De Sica, and the Italian moviegoers, simply needed.

Go back to Plate O' Shrimp

<< Home