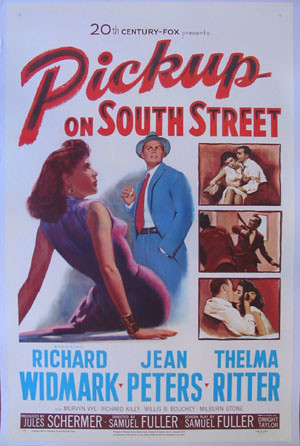

Pickup on South Street

(1953, 80 min.)

Starring Richard Widmark, Jean Peters, Thelma Ritter, Murvyn Vye, Richard Kiley, Willis B. Bouchey.

Directed by Samuel Fuller.

Widmark plays Skip McCoy, a pickpocket who, just hours out on parole for the third time, is back to his old tricks. He lifts the wallet of a woman named Candy (Peters) on the subway, but unbeknownst to him (and her as it turns out) there’s some microfilm in there that her weasely ex-boyfriend Joey (Kiley) has enlisted her to deliver to Communist- excuse me, I mean, Commie spies, though she has no idea exactly what she’s mixed up in.

What’s more, a couple of feds were following her with the intention of picking up whoever she passed the goods to and they witnessed the theft. They go to the police and meet Captain Tiger (Vye), who calls in Moe (Ritter), a professional info-peddler who sells ties as a front and whose only ambition is to buy a burial plot so she won’t spend eternity in Potter’s Field. She leads them, and eventually Candy, to Skip, who realizes that with all the interest people are showing in what he’s got, he may have finally stumbled onto his big score – and he intends to make it pay off.

This is a violent, suspenseful thriller that offers plenty of hard-boiled delights; if only it held up a bit better under scrutiny.

Let’s get the bad stuff out of the way first. Much of it, unfortunately, revolves around Ms. Peters. She’s fine in the role, and she looks great, but, while I realize characters in these films fall in love awfully quickly all the time, Candy’s affection for Skip is doubly hard to buy given that the first time she lays eyes on him, he robs her, and the second time, he slugs her in the jaw. Granted you can say that she’s playing him at first, trying to get him to give her the microfilm, but that dewy look creeps into her eye in pretty much the very next scene. Additionally when things turn tragic there are several instances, including one right in front of Skip, of Candy weeping and blaming herself, the worst part being that the smarmy creep lets her do it and even affirms her blame a little bit, regardless of the fact that in truth, the whole damn thing is his fault. (He does eventually acknowledge some responsibility, and does a damn good deed in the process, but still…)

But there’s so much about this movie that works I’m willing to forgive that which doesn’t. Fuller infuses the film with a thorough sense of urbanity. One of the small entertainments of metropolitan life is the out-of-the-way places that exist on the fringes of which most people don’t take notice, so it’s a great conceit that Skip lives in a shack on a dock down by the seaport, keeping his beer cold by lowering it in a box down into the East River. His secluded, solitary accommodations make a nice contrast to the packed claustrophobia of the subway cars where he makes his living.

The film is in part about the subculture of small-time hustlers, and it could have stood to use a bit more of this. Its eighty-minute running time keeps things taut and precise, but doesn’t leave much room for embellishment, so aside from Skip and his schtick, all we get in this respect is the great scene with Lightning Louie and his chopsticks, and Moe, the latter of whom represents one of the film’s greatest achievements. Many films about grifters feature a stock character who has been doing whatever it is they do for far too long and wants out, but as played by Ritter, Moe is the utter embodiment of this concept. Moe is tired: tired of being alone, tired of being bitter, tired of having creeps for friends, tired of having to fink on said creeps for a living. The fact that she is literally looking forward to death is a marked difference to Skip’s devil-may-care attitude towards his own way of life, and is the one thing that ends up lending him a conscience in the end, and in a rather courageous way for Fuller to have depicted it. Or rather I should say possibly courageous. (Note: A pretty important spoiler follows.)

Being the treasonous leftist that I am, I have always chosen to attribute Skip’s eleventh hour conversion from opportunistic asshole to buster of iniquitous jaws to his regret and guilt over Moe’s murder, rather than some sort of patriotic awakening. Now it could be argued that since Moe dies because of her refusal to play ball with a “commie” her resolve is just as much a part of his turnaround as his remorse, suggesting that patriotism does have something to do with it. Watch the scene where she faces down Kiley and it makes for a compelling case, but I still prefer my interpretation. For one thing Skip is consistently resistant to people “waving the flag” at him, and it’s nice to think Fuller had the balls, given the tenor of the times, not to give into what pressure probably existed then to go as up-with-America as possible. For starters the movie’s anti-communist enough without needing to drive it home by making Skip “see the light”, and to me it’s far more dramatically satisfying to have the ending, which incidentally climaxes with a bang-up brawl in a subway station (the film coming full circle perchance?), come from something deeper than a standard morale straight out of your run of the mill propaganda film.

But frankly, jingoistic or not, it doesn’t change the fact that this is a compact thriller and one of my personal favorite noir pictures.

Go back to Plate O' Shrimp

<< Home