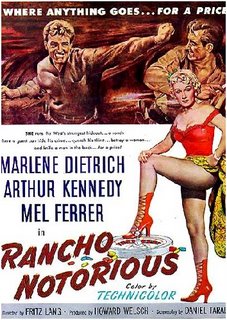

Rancho Notorious

(1952, 89 min.)

Starring Arthur Kennedy, Marlene Dietrich, Mel Ferrer, Jack Elam, George Reeves, Frank Ferguson, Francis McDonald, Gloria Henry, William Frawley, Lisa Ferraday, Dan Seymour, John Kellogg, Rodd Redwing, Roger Anderson, Russell Johnson.

Screenplay by Daniel Taradash from the story ‘Gunsight Whitman’ by Silvia Richards.

Directed by Fritz Lang.

Kennedy plays Wyoming cattlehand Vern Haskell whose fiancée (Henry) is raped and murdered by a thug (McDonald) passing through town. Fueled by rage and grief, he follows the man’s trail to a remote horse ranch called Chuck-a-Luck (named after a roulette-style game). The place is run by legendary ex-saloon girl Altar Keane (Dietrich), and doubles as a hideaway for bad guys on the lam, including her squeeze, Frenchy Fairmont (Ferrer), legendary himself for his shooting abilities. Already tense circumstances get ratcheted up when Vern finds himself engaged in an outlaw lifestyle anathema to him and at odds with Frenchy over his attention to Altar, all the while obsessed with figuring out which one of his bunkmates is responsible for his love’s death.

Once again, director Lang displays his penchant for stories about men whose reason is overpowered by their emotions. The only tie we’re shown that Vern has to his community is his fiancée, and indeed, once she’s gone, he’s pretty much in the wind, following whatever leads he can snatch out of the air as he divines the mystery of Chuck-a-Luck, told through a small series of entertaining flashbacks. It’s not that Vern doesn’t have his wits about him – he knows when to lie and what lies to tell – but the thread holding him together is a tenuous one. There’s a great moment where Vern – convinced by nothing more than circumstantial evidence that fellow ranch hand Wilson (Reeves) is his man and riled by Altar’s song about the unwanted attention of impetuous boys – charges through the reveling crowd with violence on his mind, only to be stopped when the lookout pokes his head in with a warning of approaching lawmen before anyone can see the burn in Vern’s eyes.

But the central conflict here is different than in Lang’s other films. Spurred, perhaps, by the indisputable righteousness of Vern’s cause (I’m no fan of vigilantism, but there’s no denying that the man he’s after is a bad, bad guy), Lang doesn’t feel the need to portray him as a man losing himself as so many of his other protagonists have been. Vern is all too in touch with himself – he even insists on being called by his real name at the very pseudonym-friendly ranch – and the disgust he feels for those he’s forced to take up with in his quest is largely kept in check until a scene that startles both for its suddenness and for its interesting subversion of the dynamic that usually rules characters who find themselves in the presence of Marlene Dietrich.

The story is multi-faceted and entertaining (although the narrative clunks a bit at the very end), but this is no standard western. Akin to Nicholas Ray’s similarly baroque Johnny Guitar, Rancho has a more emotionally charged story to tell and yet comes off as subtler in comparison. No exploding mountainsides here. Or exploding women for that matter. Dietrich’s sloe-eyed Weimar persona (which was a far more important factor in all but her late-career roles than her acting abilities) is firmly intact and there’s little to rival the snarling hellcat antics of Crawford and McCambridge in Ray’s film. The nods to such adult subjects as rape (the doctor tells Vern that his fiancée was “spared nothing”) and kinkiness (the human horse race) also set this apart from your standard handguns and horseshoes fare of the period, the latter possibly pushing it into the realm of deliberate camp, although that’s a point made far more, well, pointed by the presence of…the song.

Ballads are a western tradition, as well as a tradition in westerns. A whole subset of the genre was devoted to singing cowboys, after all. And in some cases a good ballad can serve to make a great film even more poignant, as in ‘Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’’ from High Noon or, in an unjustly less famous example, the George Duning-penned title song for Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma, as sung by Frankie Laine. There’s really nothing inherently wrong with Ken Darby’s ‘The Ballad of Chuck-a-Luck,’ sung by William Lee, but it isn’t hard to understand why some might find it a bit amusing, breaking in as it does in the fairly serious narrative so that Lee’s deep earnest voice can repeat ‘chuck-a-luck, chuck-a-luck,’ building up to dramatic call of ‘Hate! Murder! And Revenge!” If this were a Coen Brothers film, we’d know they were using it tongue in cheek, but with Lang it’s not so clear. Despite the dramatic nature of the film, it’s obvious that in certain aspects he’s having fun with the material, so who knows? Trying to divine his motives at this late a date may be irrelevant anyway. Giggling at ‘The Ballad of Chuck-a-Luck’ may simply be part and parcel of the same post-modern impulse that compels me to mention that this is likely the only film in history to feature appearances by Superman, The Professor and Fred Mertz.

Go back to Plate O' Shrimp

<< Home